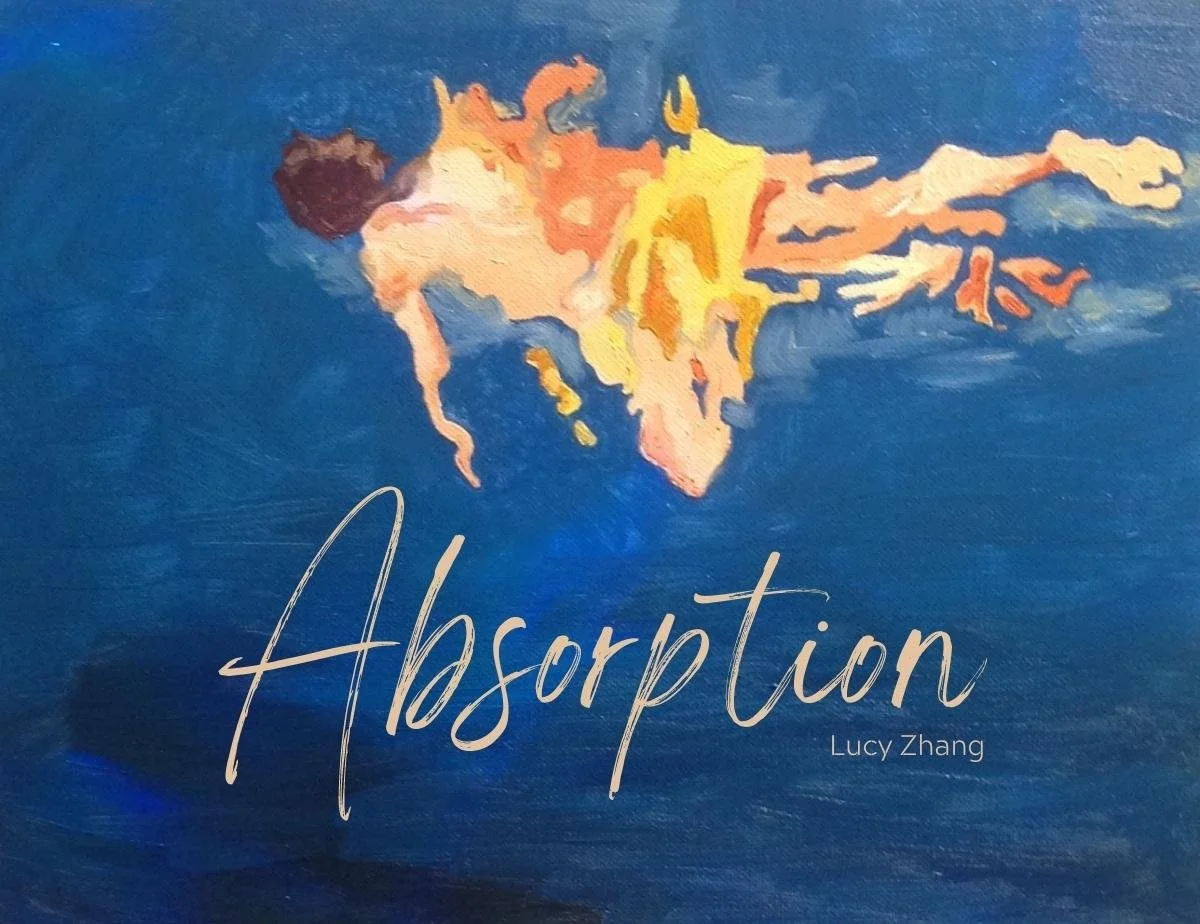

Cover art: Swim

Artist: Charity-Mika Woodard

Foreward

What draws me to micro chapbooks is the forced transparency that happens to each poem from confinement of numerical inclusion. With large collections of poetry, some poems are more engrossing than others. In Lucy Zhang’s micro chapbook, Absorption, each poem has equal ability and power to “mold glutinous rice around our bones.”

Zhang explores the essence of the latin root, absorptio; as something swallowing up; as how a body absorbs the world’s experiences; as “good as air: girls like me, slicing tissue to mush or not at all. How will you learn to chew, Ba asks. I chew with a blade.” Life lessons are chewed with sharpness, to be swallowed smoothly, to live stronger.

Literal swallowing is explored as well, there’s a large overarching theme of food absorption, perfected in the poem “Rice Cakes”: “no one watches as we stuff them down our esophagus, let it layer up & coat our bones & smile to a clean plate, our insides all glue & honey.”

Zhang documents food preparation: how water absorbs into rice, how food absorbs heat, how “in a sear, the burning comes too late, the scent an aftermath of deprotonated amino acids deglazed with sake or Pinot Noir, the taste of acid and coal and glutamates, darkened to something like death.” Within her documentation of the smallest moments, we see extremes clearly laid out, beauty and death.

Absorption highlights everyday experience to give readers a deeper sense of absorption—deeper than environment, than skin, than muscle—documenting the experience of “nitrogen crush[ing] my lungs, alveoli popping like bubble wrap.” Zhang turns the action of absorption into a poetic homage to the nanoscopic aspects of experience.

Kristiane Weeks-Rogers

June 2022

Absorption

Small hermaphrodite flowers, a fourfold double perianth, sprouting yellow to off-white petals,

hiding nectar glands curved like antlers, bearing indehiscent fruit—strip their glaucous leaves,

rip them out of the soil, pulverize until powder, dry into granules. I dissolve isatis root,

dandelion, and viola in hot water; it turns dark, the bottom of the mug an open end. I drink, never

really knowing if this’ll make me breathe easier the next time I step outside, feel the sunlight and

nitrogen crush my lungs, alveoli popping like bubble wrap. Is my blood cooled now? Heat

drained from limb cartilage? The fire doused with roots and rhizomes? We’re standing outside,

gasping for oxygen—some kind of pulmonary hypertension, stealing air the moment we peel our

faces off for the sun. Now, your hand on my forehead, does it feel like ice against ice?

The skin sticks to the pan if you’re impatient, unwilling to see the carbonyl and amino groups’

reaction through, browned and crisped crust forming a clean divide with the iron, but that sort of

time, who has it, balancing between too short and too long, too low and too high, barely skirting

carcinogens. We learned to avoid hurtful things young: stray far from intersections without

streetlights, refuse every man’s reach because there’s always one hand that’ll choke your words

from your trachea and seal your eyelids shut until you can only listen to the slurping of

premonitions, made real. The butterfly flew too close to the fire, left us with smoke and charred

chitin to drown out the stench of human feces in those hole-in-the-ground toilets; wings that

smelled like incense, we’d say. We learned to steam in layered trays, avoiding the oil and sizzle,

preserving vibrant hues, almost pastel-like, baby-like. In a sear, the burning comes too late, the

scent an aftermath of deprotonated amino acids deglazed with sake or Pinot Noir, the taste of

acid and coal and glutamates, darkened to something like death. We scrape and scrape the

bottom of the pan, trying to salvage what we lost.

As a child, I feared foxes—the ones disguised as beautiful women whose skin never suffered

under the sun’s glare and whose waists were no wider than a sheet of A4 paper—these foxes

tricked tigers into lending them their striped coats so they’d masquerade at the top of the food

chain, hopping from boulder to boulder, fearless, which made me feel bad for the tigers, now

naked cats trying to catch mice in their paws, but everyone mistook the tigers for oversized mole

rats and dispatched them with glue traps, so soon there were hardly any tigers, only foxes, which

I saw in everyone, especially my guidance counselor with her pointed nose and clacking heels—

and how she towered over me, asked me what I’d brought for lunch that day and I conjured up

pork blood, octopus tentacles, chicken hearts even though my paper bag lunch box was actually

empty and I’d sit behind it in the cafeteria and flip through apricot-colored SAT vocabulary

flashcards instead, maybe hungry maybe embarrassed definitely trying to memorize

“complacent” and “competent” and “complement” and that foxy woman told on me, and my

parents yelled, and I thought about expensive things like computers and college tuition and

treatment programs and decided to grow up, something I could surely do, just skin the fur off a

tiger and wrap it over my clavicles, turn my orange-brown striped back to the world, just like

that, until my hips widened and chest swelled and suddenly everyone could see the nine tails I

had grown while hidden away on a mountain’s slope, where jade and green cinnabar covered its

surface; yes, hidden there was a child now fully-fledged man-eater, and now I shape-shift into a

waif-like celestial maiden to seduce men and eat up their spirits like barbecued chicken hearts,

ripping them off, one at a time, until I am full.

We show our spines like a stegosaurus, mold glutinous rice around our bones & decorate them

with treasures: dried longan, dates, black sesame, adzuki bean paste, darkened with brown sugar

& oil, our backs smoothed & softened & cushioned, so nai nai will say you gained weight! &

squeeze our arm–it sinks like tofu sponge under her spindly fingers.

We soak the knife in warm water, crush rice with a wood mallet, slice it into cubes: dipped in

soybean flour, stirred with dates; no one watches as we stuff them down our esophagus, let it

layer up & coat our bones & smile to a clean plate, our insides all glue & honey. At night we slip

off our skin, peel away the rice, rub our bones down with alcohol, seal our skin back up & we

scoop the rice in our hands, pull at a red date, measure how long the rice stretches by counting

years passed since sugar rations, since milk was only for pregnant & nursing women—

generations spilled like melted lychee once suspended in ice, an eternity—so consider the

stegosaurus, a herbivore, plated with armor, tail tipped with spikes & how hard it'd be to drill

down to organs—how easy it is to lose & find our vertebrae.

We never bought a food processor so I grind pork with a knife, criss cross muscle fibers, get as

close as I can to the cutting board, knuckles battering bamboo. Ba prefers the rubber resistance of

chew but I prefer the softness you can fold inward, dissolve under teeth. Like nothing, according

to Ba. A dollop of miso, a sprinkling of bonito flakes, a glug of sesame oil—that’s not right, Ba

says. Oyster sauce and chives, nothing else is needed. But I pretend not to hear and churn until

my spirit swirls into a whirlpool of tiny nothings propping up flour crimps I pinch and seal with

water, like I’m squeezing slivers of yin out of my throat, balled up, never to spill. Ba bites. The

inside isn’t hollow; still, Ba says it’s just flour stuffed with air. As good as air: girls like me,

slicing tissue to mush or not at all. How will you learn to chew, Ba asks. I chew with a blade.

Let snow bury old Xu Fu Ji crispy peanut candies & half-digested rice. Sugar is better sent into

earth than left to grow mold in a plastic bag. They tried to send me away, you know, like snow

can hide footprints as much as it allows them to exist. Pretend you don’t see them: shadows,

imprints, like Bigfoot marched through. Life might creep under crystals, absorbing syrup,

desiccated coconut, refined colza oil, building breathing growing until their sky melts. Find me

frozen, snappy limbs like silver fish bones, before I make it over, where problems are fixed just

because we bury gold with wrappers—an unmarried scarecrow meant for mending, an

inheritance of jewels wasted. I am not grass, unintentionally weeded yet without casualties. If

only I could be like that, puncturing ice even before spring, instead I am strung like old wires on

the zither, though they sounded beautiful once, still taut against the wood board hammered,

glued, sanded in the basement, left there to play a dirge of silence, for daddy long legs & mice &

bones to pirouette. The candies flake & crumble, but I rattle against bars waiting for rain to either

flush away snow or freeze over. I didn’t eat them, the ground did, swallowed like a supernova—

is the hope, transgressions forever hidden, so I can stay.

Red

Is the rose stuffed in an Oi Ocha bottle.

Is the first blood, but not those after, oxidized and darkened. Her body moves slower than it

should, faster than she’d like, trying to clasp time in cuffs.

Is the color of the qipao she wore to her wedding banquet, after peeling off the white organza

dress, after strangling her waist with an elastic band. The strapless bodice skirts her bare

shoulders, a reminder of what she lacks.

Is the lobster after it has been steamed, crustacyanin unveiled, astaxanthin released. Not

everything dies pretty, she tells her daughter who thinks Sleeping Beauty is dead. She dreams

about scratching at a board, her body wrapped in twenty layers of silk, sealed in four coffins, one

enclosing the other, her stomach full of melon seeds that sprout and slip through the cracks in her

body so they can grow.

Is the parasol she holds over her head to block the sun. She pulls her daughter tight to her body,

under the refuge of shade, but her daughter wrenches herself free and skips into the UV. Your

skin will grow spots, she warns. Like tapioca pearls floating in milk. Like frog eggs abandoned

in pools of water, cradled by the bromeliad plant. Why do you have to carry that thing out, her

daughter says.

Is the bracelet her daughter wears when it’s the Year of the Ox, her zodiac year. The bracelet is

from grandmother, but the only reason it gets worn is because it’s too difficult to take off. At the

end of the year, her daughter cuts it off with a Swiss Army knife. Says it gets stuck in zippers

and hair.

Is the last blood and all those before. Her limbs combust at night and she pulls herself out of bed,

opens a computer, looks up pink bibs and pink stuffed toys for her daughter’s baby shower,

decides on a crimson set that might be more gender-neutral. She scavenges the cabinets for dried

ginseng root and honey dates. Packages them in a box. Tapes on a mailing address label.

Wonders if her daughter’s body has begun to burn, when she’ll realize it was always burning.

Where to grow this carriage of a pumpkin (a Rouge Vif D'Etampe not a kabocha this is not for

eating! says the fairy godmother to herself [dementia manifests like vines coaxed down brick

paths])? Behind briars and beanstalks and golden straw bale? Spray them with hydrogen peroxide

Grow them with nasturtiums Snatch a stamen from a flower and brush it over another's stigma

(who trusts natural pollination to do its course? certainly not she) It is a labor of love! The

cinder girl rides away to her fated ball in a hollowed squash and the fairy godmother tends to the

remnants of her effort (fibrous strings tossed and seeds roasted) because years of granting wishes

have made her sensitive to waste festering behind dreams rooted in sterling silver tiaras that

tarnish as soon as you forget them on the bathroom sink but {Everyone goes through this phase

Everyone dreams for the snappiness of wands Everyone wishes to see a barouche better yet a

Porsche in place of a pumpkin Everyone sprints in glass slippers though they forget to leave

breadcrumbs so they can find their way back Everyone trips their way down the stairs when

midnight strikes Everyone wonders where were they going from here?} she sprinkles sea salt

over the seeds and crushes them between her molars as she waits a few more decades when they

will come back to ask her what she regrets in life so they do not make the same mistakes Tell me!

they demand in their duchesse satin stylized with floral motifs someone must have spent a

lifetime appliquéing and the fairy godmother pours a cup of chrysanthemum tea as they sit by the

garden (lately she has started growing sugar pumpkins and butternut squash and kabocha which

eat into her Rouge Vif D'Etampe patch so now there is only enough space for one carriage per

year) and plucks a ripe squash the weight of a newborn and perfect for pie would you like to take

one back?

You began as a grain of rice at the bottom of a sack, raw and starchy. One year of congee, fried

rice, furikake rice, plain rice to hollow out. I rolled you between two fingers: white dust flaking

like dried Elmer’s glue, milk bleeding from a nipple, counting droplets a metronome—taping can

encourage lactation, can patch a hole. I tossed you back in, stuck between flaps and threads. I

flattened the edges and wrinkles best I could before fitting the near-empty bag in the trash can,

our Glad substitute. You rested beneath fish bones, onion peels, empty Yakult bottles. Beneath

bloodied tissues, band-aids, Maxi Pads. Hair swept and tangled in clumps, nails split like roads,

globs of skin cells scratched and peeled from eczema-coated hands. Dried gothic-style roses

(used to be fresh, but always dead, yeah? once they’re cut, they’re dead), sponges soaked in oil,

one negative pregnancy test (don’t think too much), a trickle of urine. I fed the world to you.

Flies hovered, like black sesame stars in arm’s reach. Again, I lifted the lid and pressed down to

fit another layer: papery eggshells, cracked coat hangers, moldy excisions of potato. As a grain

of rice at the bottom of a sack, unswollen and unsplit, you stayed.

Acknowledgements

The Cortland Review: “Ban Lan Gen”

The Shore: “Maillard Reaction”

Figure 1: “The Fox and the Tiger”

Welter: “Ba Bao Fan”

SOFTBLOW: “Rice Cake”

The Portland Review: “Jiaozi”

Serotonin Poetry: “Ice Burial”

Chestnut Review: “Qualia”

DIAGRAM: “The Carriage Became A Pie”

Wax Nine: “Teach Me All There Is to Know”

Absorption

Copyright © 2022 Lucy Zhang

Cover art: Swim by Charity-Mika Woodard

Cover design by Diana Baltag

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or republished without the prior written permission of the publisher, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical reviews and certain other noncommercial uses permitted by copyright law.

Harbor Review

Joplin, MO 64870

harborreviewmagazine@gmail.com

www.harbor-review.com

Lucy Zhang

Lucy Zhang writes, codes and watches anime. Her work has appeared in The Offing, The Rumpus, EcoTheo Review and elsewhere. Her chapbook HOLLOWED is forthcoming in 2022 from Thirty West Publishing.

Find her at https://kowaretasekai.wordpress.com or on Twitter @Dango_Ramen.