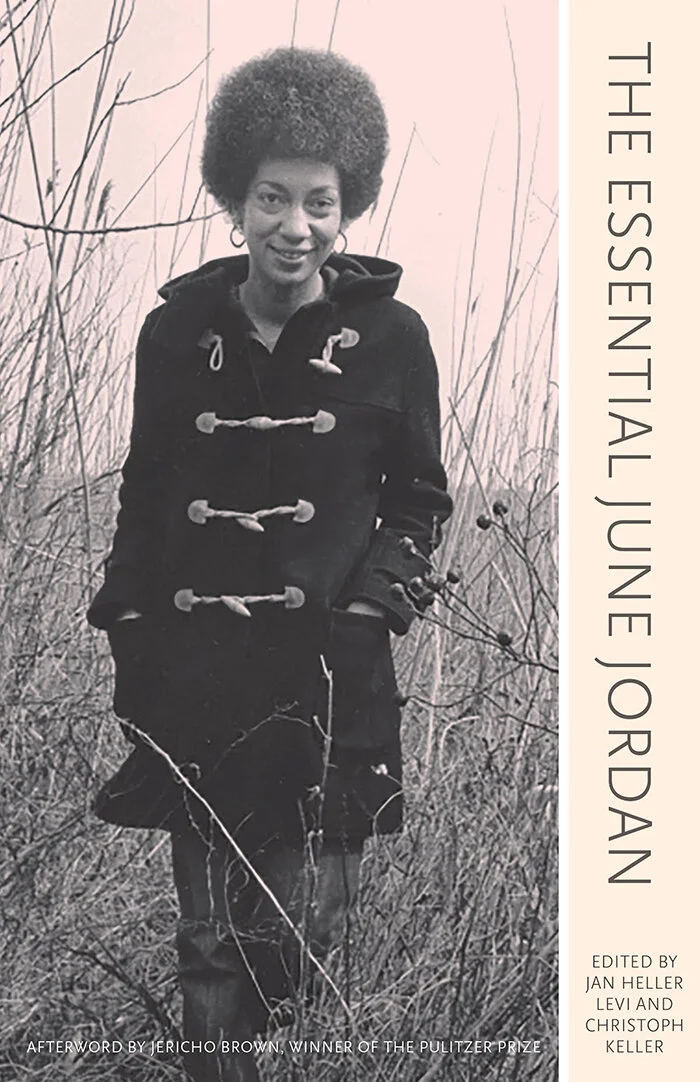

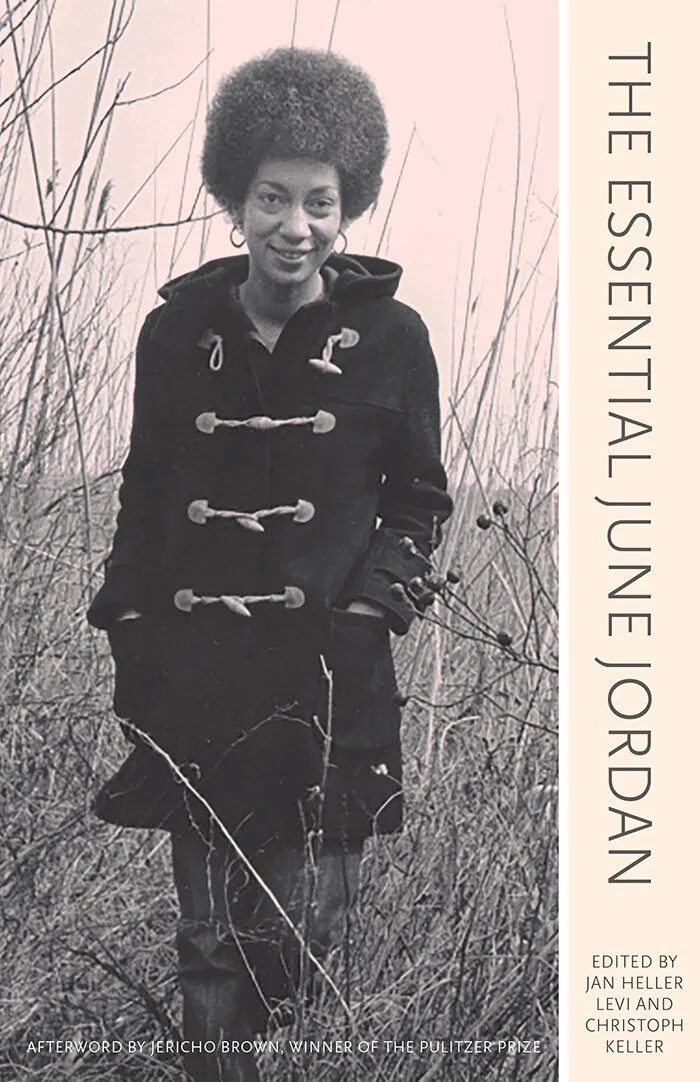

THE ESSENTIAL JUNE JORDAN

EDITED BY JAN HELLER LEVI AND CHRISTOPH KELLER

REVIEW BY JASON M. THORNBERRY

The poet June Jordan did not live to see a policeman kneel on George Floyd’s neck. Nor did she see spontaneous protests erupt in cities across the world, in response to Floyd’s death. Jordan did not observe the National Guard’s deployment to Lafayette Square in D.C., or the peaceful protest they crushed to facilitate a mercenary photo opportunity for an openly bigoted American president. Jordan did not see the sacking of our nation’s capital. She did not see the same National Guard stand down, as embittered, mostly white men staged their own photo opportunity in the halls of congress, smearing feces, smashing windows, assaulting police.

Though Jordan did not live long enough to examine these recent societal fissures and recognizable commemorations of white supremacy, she understood their causality, their roots, their source. As a Black woman, the America Jordan experienced convinced her incidents like these are not trivial. “I don’t mean to be an alarmist or anything,” she said, “but I really do think that this is an apocalyptic moment in our history.” Jordan said this in 1981, before Rodney King. Before George Floyd and the murder trial that could prophesy possibilities of accountability and reconciliation.

A new collection, The Essential June Jordan (Copper Canyon Press, 2021) showcases her earliest poetry—works like “Who Look at Me,” from 1969. It also focuses heavily on her forty years of groundbreaking verse. Jordan says poetry is “a political action undertaken for the sake of information, the faith, the exorcism, and the lyrical invention, that telling the truth makes possible. Poetry means taking control of the language of your life.” A facility with language came to Jordan early. She recalls her father, a Jamaican immigrant, forcing her to read Paul Laurence Dunbar and Shakespeare when she was a child. Jordan notes that she was too young for some of the material. “He was so premature,” the poet says of her father, “in his expectations that he gave me all these things to read that I really could not understand. But,” she laughed, “I had to memorize them anyway. That meant, that I had to acquire the words, one way or another. I acquired them mostly by sound. The music of the language saved my neck as a kid.”

In her poem, “Shakespeare’s 116th Sonnet in Black English Translation,” Jordan examines the musicality of Shakespeare’s attempt to describe the immeasurable qualities of love. Shakespeare says: “Let me not to the marriage of true minds / Admit impediments. Love is not love / Which alters when it alteration finds, / Or bends with the remover to remove.” Jordan reimagines his words:

Don’t let me mess up partner happiness

because the trouble

start

An’ I ain’ got the heart

to deal!

Because Jordan was also expected, as a child, to memorize portions of the Bible, tasting its cadences and rhythms, she considered herself a poet at an early age. Growing older, Jordan still saw herself that way. “I don’t think I ever wanted to be a writer,” she said in 2000. “The writing I’ve done, other than poetry, came much later. Whether I’m writing a libretto or political essay, or even the one novel I put out [1971’s His Own Where]. I was writing as a poet.”

Jordan’s greatest strengths lie in occupying the voices of Black Americans through her “commitment,” as Jericho Brown says, “to Black vernacular.” She also pulls the reader feet first toward a fiery examination of hypocrisy. In “Poem About Police Violence,” Jordan says:

Tell me something

what you think would happen if

everytime they kill a black boy

then we kill a cop

everytime they kill a black man

then we kill a cop

I lose consciousness of ugly bestial rabid

and repetitive affront as when they tell me

18 cops in order to subdue one man

18 strangled him to death in the ensuing scuffle (don’t

you idolize the diction of the powerful: subdue and

scuffle my oh my) and that the murder

that the killing of Arthur Miller on a Brooklyn

street was just a “justifiable accident” again

(again)

Some believe Floyd’s existence as a Black man in an openly bigoted society preordained his collapse in the street beneath a white cop’s knee. In “Poem About my Rights,” Jordan describes her own struggle to make sense of that grotesque reality:

Even tonight and I need to take a walk and clear

my head about this poem about why I can’t

go out without changing my clothes my shoes

my body posture my gender identity my age

my status as a woman alone in the evening/

alone on the streets/alone not being the point/

the point being that I can’t do what I want

to do with my own body because I am the wrong

sex the wrong age the wrong skin and

suppose it was not here in the city but down on the beach/

or far into the woods and I wanted to go

there by myself thinking about God/or thinking

about children or thinking about the world/all of it

disclosed by the stars and the silence:

I could not go and I could not think and I could not

stay there

alone

as I need to be

alone because I can’t do what I want to do with my own

body and

who in the hell set things up

like this

Memories of riots shaking Los Angeles following the acquittal of the cops who beat Rodney King in the street like a dog make us wonder, will America ever learn from its past? Systemic racism, embedded unfathomably deep, cannot be healed from the historic guilty verdict in the trial of Floyd’s killer. Awaiting true justice—which extends far beyond the conviction of one wicked policeman—I find some small comfort in Jordan’s words about the power of poetry. She said: “Good poems can interdict a suicide, rescue a love affair, and build a revolution in which speaking and listening to somebody becomes the first and last purpose to every social encounter.”

May, 2021

Jason M. Thornberry

Seattle writer Jason M. Thornberry’s work appears in The Los Angeles Review of Books, Adirondack Review, Entropy, Route 7 Review, Litro, In Parentheses, and elsewhere. An MFA candidate at Chapman University, Jason taught creative writing at Seattle Pacific University. He reads poetry for TAB: the Journal of Poetry and Poetics.