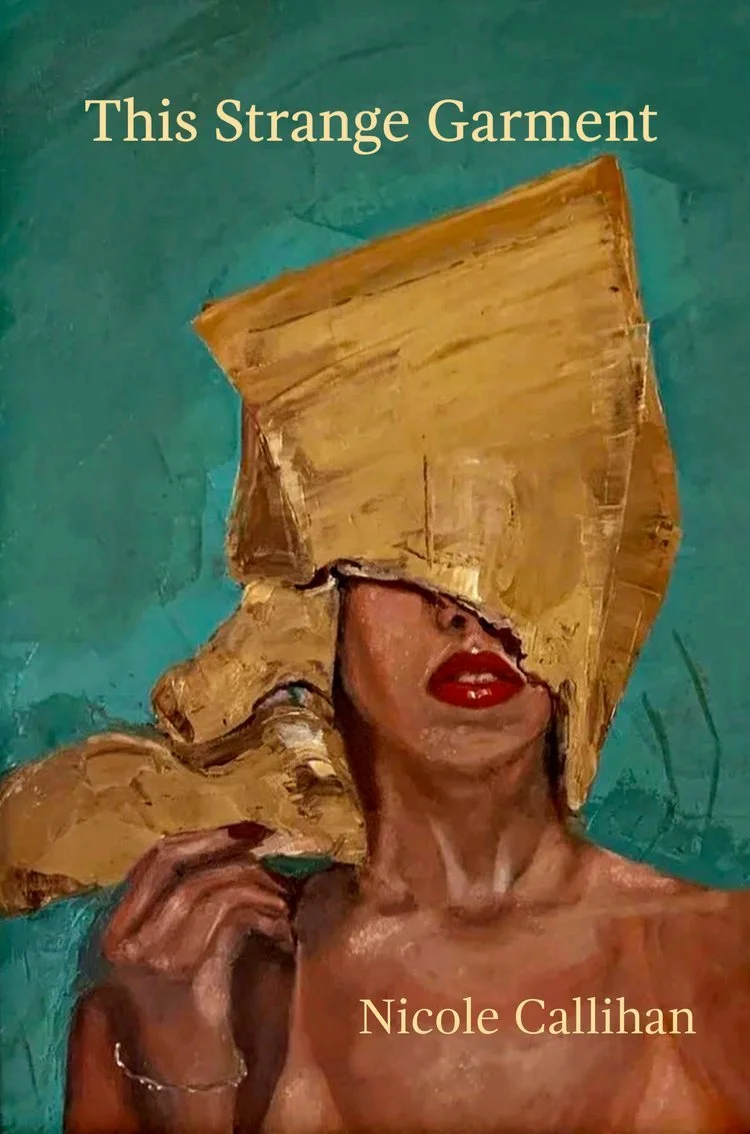

This Strange Garment by Nicole Callihan

Review by Melissa Ridley Elmes

“In the beginning, there was a body,” Nicole Callihan writes in “The As If Of,” chronicling the changes wrought to that body through a cancer-related double mastectomy and TRAM reconstruction alongside considerations of the temporary nature of the human body and its parts and our emotional attachment to them—recalling games of “where are your eyes?” and “I’ve got your nose” played with children and revealing anxieties over whether the post-cancer body under scrutiny will still be considered desirable. Beginning with images of the surgical removal and replacement of her bellybutton during the procedure, Callihan concludes this poem with, “If you say belly button over and over, it’ll start to sound like / something else. Like saying hydrangea until it becomes a bomb.” The movement in this poem from experience and observation to meditation and introspection, its humor tinged with darkness, and Callihan’s skillful and playful engagement with language are hallmarks of the overall collection, which chronicles with unflinching realness the poet’s experience undergoing breast cancer diagnosis and treatment during the early stages of the Covid-19 pandemic.

“Do you ever feel like an alien?” Callihan asks Cliff, the deliverer of her radiation treatment, in “To Get to the Other Side.” "I am feeling more and more like my childhood alien abduction dreams were actually dreams about middle-aged cancer treatment.” She walks us through her thoughts and observations of that alien body and the spaces it occupies—home, hospital, various specialist offices—in the five sections of this collection: before surgery, in Part I’s “Imaging,” as radiologist Galena goes about her work (“I think about the surgery/ I think/ I want them/ to take both of my breasts/ just take them/ leave long scar”); just after surgery in Part II’s “Woman With Bright Spots,” when Vlad, another radiologist, asks her if she can move her arms a little higher over her head (“I can’t, I say. Only this high, I say, which is not very high. The / scars aren’t even really scars yet, still just wounds”); in Part III, dealing with medically-induced hot flashes in “The Alternative” (It is something / to be on fire, my last best burning / in the winter. It is something / for the heat of a life to collect and collect / in the small of your back, the blades / of the shoulders”) and the results of radiation in “The Skin Right Now” which, the doctor tells her, “is more like paper / than skin; it can so easily tear.” Part IV offers a series of poems featuring skillful wordplay juxtaposed alongside raw and direct chronicling of the side effects of treatment and surgery gone awry; in “The Pain Scale” Callihan notes that “Nearly always, I was a six, / somewhere between a five and a six” then declares “I’m ready / for a pleasure scale, and not moderate pleasure, I want / severe. Severed but raptured. Not comfort but pleasure. / Pure unadulterated pleasure. Ten, I want to say, ten.” Part V details the long-term treatment and aftereffects, the hope and uncertainty that come with routine monitoring activities after a cancer diagnosis and treatment; in “Bloodwork,” Callihan writes:

It’s the next August, what I would have called “a year from now”

a year ago.

If a year ago was a year from now, then.

I’d like to be in the pool with Ella, holding her body to help her

float, watching her bat her eyes at the sun, the sky as blue as this

tourniquet.

Has it passed? Am I through?

I could spend a decade writing odes to the sound of the air conditioner.

The tension here between desire to believe she is safely on the other side and fear that may not be the case, and the desire to make plans and think of the future even as she is currently having blood drawn to determine whether that future is in jeopardy, are palpable, raw, and authentic.

One of the many beautiful aspects of this collection is that while Callihan must of necessity undergo these treatments and navigate her emotions and psyche as an individual, she is never alone and she knows it: in addition to Cliff, Galena, Vlad, the anesthesiologists, nurses, and other specialists she encounters in her hospital visits, her mother, husband, and children, are all there alongside her through this experience, and her students keep her engaged beyond the world of her diagnosis and treatment. Yet, the presence of people is also a sharp reminder of the ongoing pandemic, as seen in her detached virtual follow-up visit with her doctor in “More Like Wings,” and in “Everything is Temporary,” in which she gently confronts a woman on a train who removes her mask to demonstrate her friendliness (“I have breast cancer, I say, and really don’t want to deal with / Covid during my surgery.”) The interdependence of people, the ways we can support and, however inadvertently, cause harm, to one another, are on full display throughout these poems.

Facing a potentially deadly illness brings with it a built-in opportunity for self-reflection and changing one’s mindset; opportunity Callihan appears to have embraced. In “The Extravagant Stars,” she notes,

When I was writing about my terrible late-term miscarriage, I gave

a reading on the Upper East Side.

Several women came up to me to tell me I was brave. So brave,

they said.

I didn’t want to be brave; I wanted to be brilliant.

In hindsight, this strikes me as incredibly dim-witted.

1 in 1 woman will look back on something and feel foolish.

Now, I will take brave any day.

And so she has “taken brave,” in penning and publishing this very human collection of poems about the mutilation and devastation wrought upon her physical form by cancer, and the emotional resilience this experience has demanded of her.

This Strange Garment is a bravely vulnerable poetic memoir laying bare the fear, anxiety, anger, sorrow, and hope that accompany a cancer diagnosis and treatment journey. More, though, this is a powerful book about mortality, trying to make sense of the human condition and understand what is happening to and within an altered body housing a single life. Read this book with tissues at hand, particularly if you or a loved one has undergone cancer treatment.

Melissa Ridley Elmes

Melissa Ridley Elmes is a Virginia native currently living in Missouri in an apartment that delightfully approximates a hobbit hole. Her poetry and fiction have appeared in Black Fox, Poetry South, Cathexis Northwest Press, Red Coyote, Haven, Star*Line, Eye to the Telescope, Spectral Realms, and various other print and web venues. Her work has been nominated for the Pushcart Prize and the Science Fiction Poetry Association's Dwarf Star and Rhysling awards for best shorter speculative poem, and her first collection of poems, Arthurian Things, was published by Dark Myth Publications in 2020 and nominated for the 2022 Elgin award.