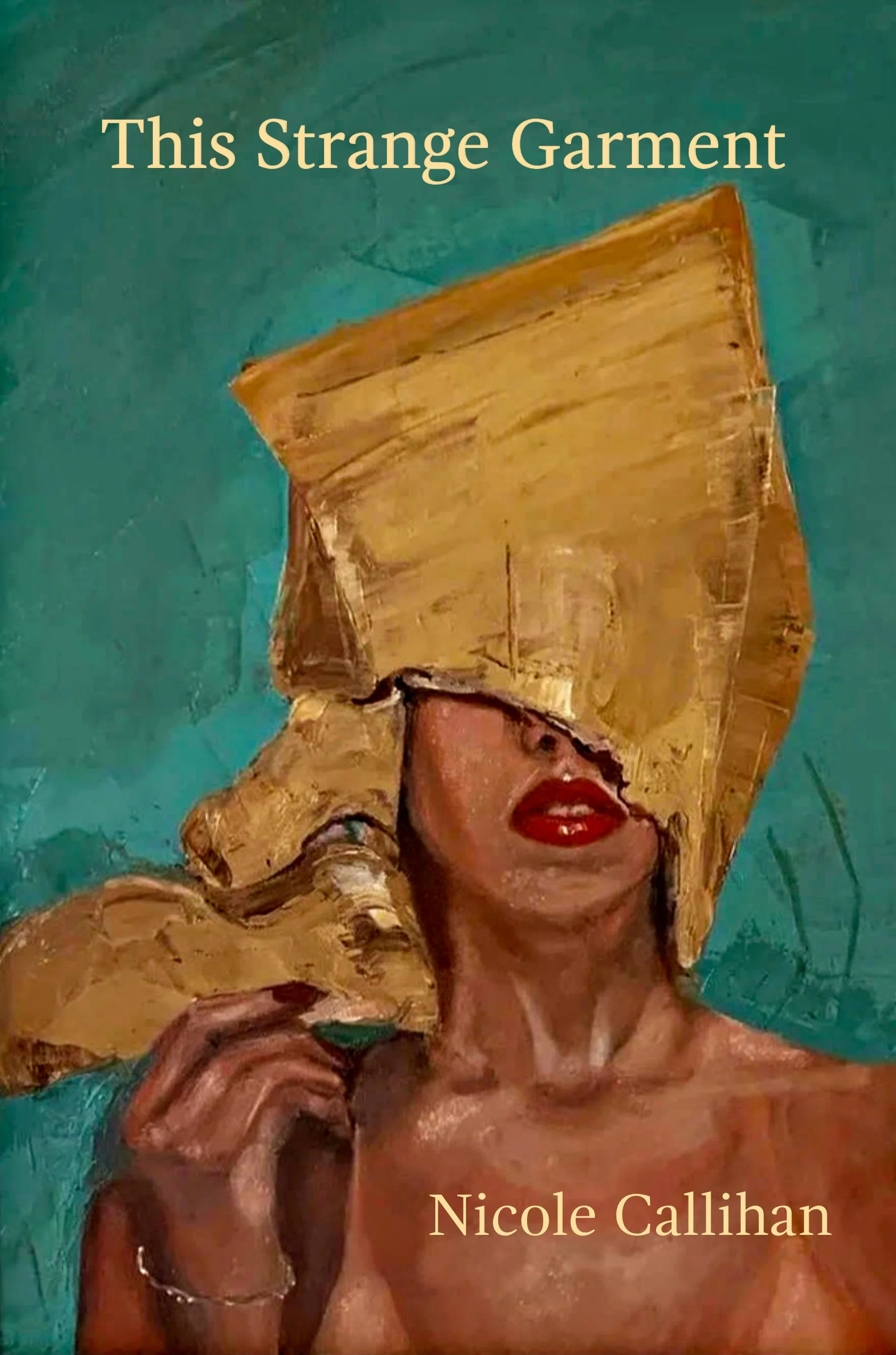

This Strange Garment by Nicole Callihan

Review by Sonia Greenfield

Can we just say straight away that Nicole Callihan’s This Strange Garment isn’t a cancer book, per se? Instead, let’s say that breast cancer is the occasion for the book. Thus, and by all means, if you’re specifically seeking a book about how a cancer diagnosis and treatment triggers all the big questions about mortality, then seek out this book. However, breast cancer is the circumstance from which the book arose. It’s important to avow this, because I don’t want readers to reject the book out of hand because they don’t want to read a “cancer book.” I don’t want the readership for this book limited to just women, and especially women with some experience of cancer. The book is about more than this.

The speaker of the poems in This Strange Garment stares down her own mortality but understands that, despite the limits of her existence, she must continue with the work-a-day elements of living: caring for children, spending time with friends, witnessing the beauty of the changing seasons and how it also, inevitably, marks the passage of time, which, when faced with the possibility of an early demise, becomes especially a complex blessing. As a result, the tone of the book is warm and familiar and, yes, existential.

Indeed, in This Strange Garment, there’s a decided avoidance of grandiosity in Callihan’s poems. Take, for example, the poem “A Difficult Day,” wherein the speaker discusses lice, stained panties, dog diapers, and rejected (declined!) poems. The poem steers away from majesty and gets dead honest about how life can be: base, banal, and as the title offers, difficult. Written as a prose poem, it makes reference to another poet who uses his own name in poems, so when it ends with “My god, how lonely life can be, how,/mostly, Nicole, it feels like sitting on a toilet, wiping and/wiping, until you can no longer see the blood,” we’re reminded that poems can be deeply satisfying when they speak truth with a kind of plainness of language so long as they’re clever. I would like to suggest that Callihan, in general, is a very clever poet.

Lest you’re worried, from my review so far, that the book eschews beauty in exchange for truth, you’d be wrong there, and I’m sorry for misleading you. In fact, the collection has great moments of beauty, whether manifested through language or image. But let me address these two things separately and harken back, again, to Callihan’s cleverness with language. If word play and the chiming of words excites you, as it does me, you will find Callihan’s poems satisfy something deep within the part of the brain that thrills at the sound of things. Take the poem “The Alternative”:

Having woken in my own hot arms,

my own hot body clinging to the sheets,

and the sweat of me, and the snow

beyond the snow, beyond the snow

out the window, I strip naked,

lie on the marble, let the cool of it

move to my bones. It is something

to be on fire, my last best burning

in the winter. It is something

for the heat of life to collect and collect

in the small of your back, the blades

of the shoulders, a kindling, a kinder

reminder….

There’s a galloping cadence here built of clauses and enjambment. There’s word repetition. There’s words that riff off each other, and there’s the unexpected surprise of rhyme. This is just one example of how Callihan works with her medium. In the poem “Being that it is late,” Callihan ends each line with the word “late,” so that the poem’s rhythms become incantatory:

that it is already too late,

that is was always too late,

that the day had become late,

and then the night, too, was late,

and now morning, but late

morning, but morning late

enough to be nearly noon, late

in the curve of the sky, late

in my lazy walk to the train, late

with its slate roof, its roses so late

as to be dead on the vine, late…

These are just two examples of how Callihan uses her medium playfully—this is one her consistent strengths as a poet. For the reader, this kind of play keeps the pages turning, because you just don’t know what surprise you’re going to get in the next poem and the next after that, and so on.

Speaking of play, it should be mentioned that Callihan employs wry humor when dealing with her topics, which could have been dealt with more heavy-handedly, but thank god they were not. In fact, she balances gravitas and levity well in this collection, because when faced with our inevitable demise, whether sooner or later, sometimes we will cry about it, and sometimes we will laugh about it. The crying part is the unstoppable undercurrent of This Strange Garment, the laughing part is the sugar that makes the medicine go down. Take the poem “Eighteen months later I find a tampon”: …My anesthesiologist/looked like Keanu Reeves w/ a beehive/and asked me to count backwards from ten./I was all, are you wearing eyeliner, ten/nine, eight…” or in “To Get to the Other Side”:

…I am feeling more and more like my childhood alien

abduction dreams were actually dreams about middle-aged cancer

treatment. “Like you’ve taken me from a field of poppies,” I say,

“and are performing bizarre intergalactic experiments on me.”

Cliff laughs and secures my arm in the vice. He closes the twelve-

inch steel door behind him. Once I’m in the radiation tube,

I’m not supposed to think about Marie Curie’s cataracts or her

fingernails falling off or the fact that her casket is made of lead, so

instead I repeat, over and over, Healing Radiant Light, Healing

Radiant Light, and when I get bored of repeating Healing Radiant

Light, I make up jokes instead. Horse walks into a bar with a

Camel hanging from his mouth. Bartender says, Need…A…

Healing…Radiant…Light?…

These are just a couple examples meant to illustrate Callihan’s wit, but it shines throughout this collection.

But back to beauty. It functions in this collection as we experience it while moving through the world. We are picking up groceries, or we are picking up our children, or we, like the speaker of these poems, are negotiating the seemingly never-ending treatments for cancer, and from all this executive functioning of forward momentum, startling moments leap out at us. Well, those of us who are looking, and especially those of us who are looking for poems in our piles of dirty laundry. Take the poem “Sunday Morning”:

There was god

the was in the peaches

in the cobbler, and the god

in the rosebuds in the glasses

on the table where the chicken,

fried, swam in the syrup

from the waffles, and the god

in the sweet tea, and the god

of my daughters laughing, the god

of all the women opening their blouses,

all the women saying, you’ll be okay, honey,

and the god in the scars,

and the god in what got cut out,

or what would soon get cut out,

and the god of the sun

on my face, while the breeze,

was god, yes, my god , the breeze.

A reader will find both lineated poems and prose poems in this collection, and the variety of form speaks to the complexity of content. Though this book is a vehicle for the speaker to work through breast cancer and its treatment, breast cancer and its treatment is the occasion for poetry that tries to spell out the messiness of life and the fear of death. Thus, as I said in the opening paragraph, this is not a one-note collection about cancer. Or, perhaps, it’s about the way, when one is faced with anything, really, that has the potential to kill us, we find ourselves asking the big questions about existence while continuing to exist where we are. Read this book as talisman against and guidebook for contending with the abyss. Yes, do read this book.

Sonia Greenfield

Sonia Greenfield (she/they) is the author of two recent collections of poetry, All Possible Histories (Riot in Your Throat, December 2022) and Helen of Troy is High AF (Harbor Editions, January 2023). She is the author of Letdown (White Pine Press, 2020), American Parable (Autumn House, 2018) and Boy with a Halo at the Farmer's Market (Codhill Press, 2015). Her work has appeared in the 2018 and 2010 Best American Poetry, Southern Review, Willow Springs and elsewhere. She lives with her family in Minneapolis where she teaches at Normandale College, edits the Rise Up Review, and advocates for neurodiversity and the decentering of the cis/het white hegemony. More at soniagreenfield.com