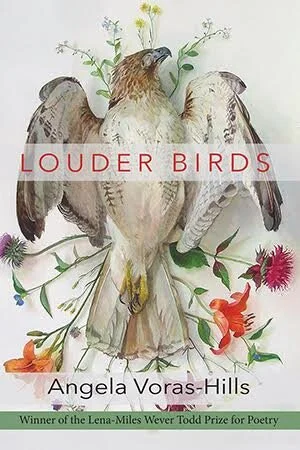

LOUDER BIRDS by ANGELA VORaS-HILLS, Reviewed by CAMERON MORSE

“Retrospective,” the first poem in Angela Voras-Hills’ debut poetry collection, Louder Birds, warns us “it’s impossible to navigate” the landscape we’re entering. She’s right—the book has no section breaks to structure our experience, which lends to an immersive read. The landscape is the American Midwest. It’s a literal landscape but, more importantly, a moral one in which we are unsure of our footing. In “At the Periphery, Where Life Hums,” the Bible’s pages are blank. The Good Book is at once vacuous and immovable. In its weight, it “cannot be removed from the house.” The idea of heaven is at once “ridiculous and comforting.” We want to offer our children the comfort of an afterlife we’re unable to believe in.

There is, in Louder Birds, a submerged narrative of conception, pregnancy, and childbirth. These events occur there in their natural order and always in a natural context. What complicates a pregnant woman’s natural desire for her unborn baby to be unharmed by a fall is the knowledge that children innocently mistake toads for frogs and throw them to their deaths in pondwater: The baby will grow into one such child.

In Louder Birds, human reproduction goes hand in hand with the disastrous environmental effects of human incursion into natural habitats and general run of the earth. This happens perhaps nowhere more convincingly than in “Unfurling” where the burning of contractions in labor parallels seasonal fires that shrivel earthworms, silence crickets, and entomb an opossum in the laundry room, “curled into a ball behind the dryer.”

Like a war correspondent, Voras-Hills writes from the front lines, or the trenches, in the conflict between the human and nonhuman forms of life on this planet. Her relentless descriptions of animal death and carnage in the context of pregnancy and childbirth suggest a moral dilemma: How do we affirm human life when procreation results in the mass extinction of the majority of other forms of animal life? “We are told to be fruitful,” she writes, alluding to Genesis 1:28. Then, in “When We Were Prey to Nothing,” an address to a newborn:

But when we were prey to nothing,

we left fields and orchard untended—

they withered as we slept

in full sun. And so it is:

you’ll grow into your skin

though the flesh of fruit

picked and eaten from every tree.

February 2020

Cameron Morse

Cameron Morse is the award-winning author of Fall Risk (Glass Lyre Press 2019). His subsequent collections are Father Me Again (Spartan Press 2018), Coming Home with Cancer (Blue Lyra Press 2019) and Terminal Destination (Spartan Press 2019). He lives with his wife Lili and son Theodore in Blue Springs, Missouri, where he serves as a poetry editor for Harbor Review.